The third novel in the Alexander Webb series is complete. By way of a taster I thought you may like to read the first few chapters.

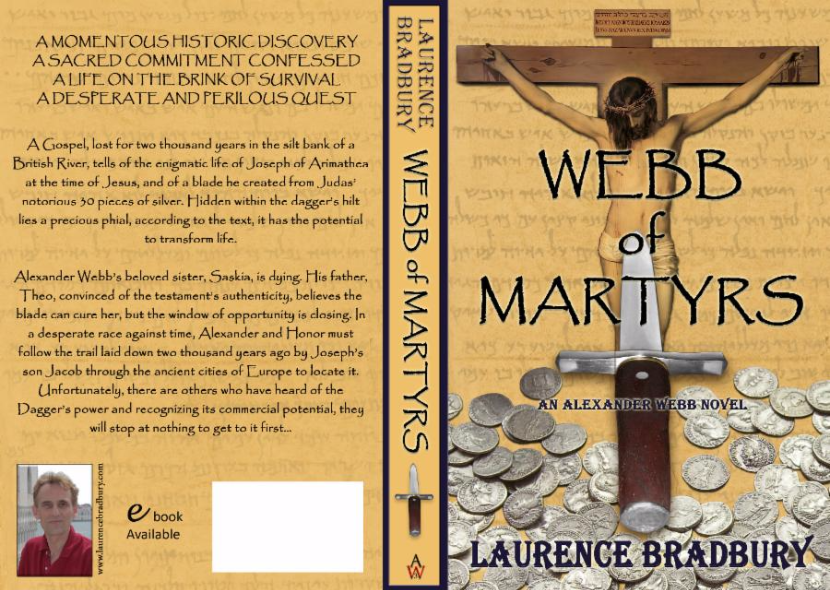

(Prototype Cover Artwork)

1

The Storm

54 AD. Sabrina River Estuary, Britannia

The pathway from the church settlement to the estuary shore sucked and slurped beneath his sodden leather sandals. His legs ached, his breath laboured and every fibre of his being fretted.

In the depth of his soul he knew they’d left it too late. If only he had discovered the threat an hour earlier, even half an hour would have helped, at least that would have given them a fighting chance.

With every stride Joseph cursed his incompetence.

He’d seriously underestimated the time it would take to usher two hundred men, women and children to the comparative safety of the boats. All about him soaked infants cried, weary mothers comforted and anxious fathers, wearing thin masks of bravery, affirmed the need to keep moving as swiftly as possible.

In all of his seventy years he’d never experienced a natural onslaught the like of this, let alone seen such impending menace in the skies.

A blinding flash and another tremendous crack of thunder clashed overhead. The awesome intensity of the clap made him flinch and over the roaring gust it was evident he wasn’t the only one to find the alarming capacity of the storm terrifying. Buried within the sheets of torrential rain and muffled by the wind’s howling voice, he could hear the whimpering unease of many others.

Soon the path ahead would be all but indistinguishable from the marsh, thank God for the planted stick markers that showed the way.

An hour’s slog and they were close to shore, but far from safe. Just one step to the left, or to the right, and any of them risked venturing into the treacherous boggy ground that surrounded them, swampy viscous swathes of mud, capable of snaring an ankle up to the calf.

The procession stalled again. A woman this time, barely visible through the deluge. She was on her knees, fishing with her hands in a path-side pool. Her bundle, containing everything she owned, had unravelled from her yoke and spilled its contents into inky blackness. ‘Help me!’ she pleaded.

Her husband urgently and forcibly dragged her to her feet. ‘It’s lost. Leave it. We have to keep going, they’ll be here any second.’

He would have liked to have helped her, but recognised her husband was right.

At daybreak Joseph had followed the legion’s tracks. Expecting at least a day’s march to the assembled battle lines, he’d been stunned to find them barely an hour from the settlement. A handful of minutes on horseback. He’d run back pell-mell to galvanise the community’s evacuation. With over half of his flock either old or infirm, it took forever.

From bitter experience, he knew, all challenges to Roman authority were dealt with swiftly and decisively. On this occasion, considering the extent of the tribal uprising, the reprisals would border on devastating. Securing his flock on the estuary’s far bank was therefore necessary, if not imperative to their continued survival. With more time and less pressure he would have preferred to have taken them further upstream to where it narrowed. A safer crossing. Unfortunately, time was not on their side.

He swept a weeping child up into his arms and wrapped his cloak around her. He could see in her eyes her lack of understanding. She couldn’t fathom the reason for their flight and the need to leave the comfort of her home to race aimlessly through a raging storm. She had no concept of freedom or of the constraints Rome’s latest dicta imposed on the people that had raised her. At the proclamation’s heart lay the emperor’s desire to abolish any religion not sanctioned by Rome. The order had been resisted with a vengeance by all but the most timid of tribes.

If only the Durotriges and Dumnonii chief’s had heeded his warning and agreed to perform their heathen rights in secret, much misery and loss of life could have been averted. He’d tried earnestly to caution them, tried to make them see reason. In a way he could understand their reluctance and bravado. Without having seen, first hand, the efficiency and deadly ruthlessness of a massed legion, he too would have had difficulty believing it.

The sun, if it were possible to see it, would shortly reach its zenith. Consequently, the action against the conjoined tribes was almost certainly over and the second Augustan Legion inevitably victorious.

Dozens of scouting parties would have been dispatched immediately following the conflict: Mounted patrols, tasked to track down and punish tribal deserters for fleeing the field of battle. He’d witnessed the process countless times in Judea, it was to be expected. Like so many things, it was the Roman way.

The path ahead broadened. Wind-harried twists of sheeting rain chased one another through the thick reed beds, and peering through the gaps between them, he could just make out the boats. Those at the front of the line were already clambering aboard and preparing to push off into the squall.

At this crossing point in the estuary it was hard to say if it was a vast river or the sea. On any other day, the rise beyond the northern shore would have been discernible, even through a morning mist. Not today though. Today the impenetrable conditions made sight of it impossible.

Dense rainfall, gusts to gale force and choppy waves dominated, potentially making the crossing treacherous. Joseph assessed the waves pounding the shore. It was evident they held enormous power and certainly qualified as deserving the respect of even the most seasoned of sailors. Normally this would be a gentle three-hour row; today they’d be lucky to make it in four, perhaps even five.

In the limited visibility, navigation would also be a problem. Without constant vigilance they could easily find themselves heading back the way they came. Fortunately, if they kept the onshore storm at their backs there was no risk of getting lost. The further up stream they travelled, the closer drew the banks. The north shore would then be obvious.

Shivering and drenched to the skin, Joseph prayed anxiously for the safety of his family as the second-to-last carvel hulled craft disappeared from view. At his insistence, his wife Miriam and son Jacob had accompanied the settlement’s orphaned children.

‘Head up river, keep them calm and well in-board,’ he’d advised over the strident buffeting wind. ‘I’ll see you on the other side.’

With his blessing, sealed with the sign of the cross, seven of their sturdy diminutive fishing vessels had now departed. Twenty five in each, surrendered to the mercy of God and the skill of their crews. His would be the last to leave. At departure, each boat’s leader had been given the same instruction: They were all to assemble at sundown on the docks that served the garrison town of Venta Silurum.

Through his feet he could feel the drumming of hooves. Then shouts and whinnies reached him, carried on the westerly gusts. The Roman patrol was perilously close.

‘There’s not much time, cast off!’

Three rows of oars rammed overboard into the liquefying sand searching for purchase, punt poles intent on pushing them free.

Alone on shore, Joseph heaved mightily against the bow to free the bogged keel. With a rising wave of panic he called out, ‘Simon, you need to help me. I can’t budge it.’

Leaping from the gunwales with a soaking splash, Simon rushed to his side, rammed his shoulder against the prow and together they pushed. On the third attempt, after another count of three, he heard it, the squelching sigh of suction-release emanating from the boat’s underside. He could feel the abrasive rush of sand against wood. It was free, just about to float.

‘Keep going.’

Another shove and it was knee deep in water, deep enough for them to climb in.

Splashing through the shallows he helped Simon aboard, then glad to be finally rid of the weight, slipped the leather strap of his precious lead canister over his head, tossed it up, hooked his right foot over the side and rolled himself onto the foremost cross plank.

‘Row!’ he demanded. ‘Row for your lives.’

A volley of pilum javelins and combat arrows pierced the air as the patrol hit the beach.

They were too close to shore to avoid them.

Wails of pain and panic ran out from the stern. Four projectiles had struck home.

With an expression of shocked astonishment, their principal church craftsman toppled backwards and slumped to the hull, impaled in the chest. One of the rearmost oarsmen had been hit in the arm and two of the women, shying from the onslaught with their backs turned towards it, had been hit. The youngest, a mother of two, screamed at the sight of the arrow protruding from her exposed waist and then squealed again louder at the blank dying face of the woman beside her, pinned through the neck.

Anguished, Joseph howled ashore, ‘Stop! For the love of God, we are peaceful people! Please stop!’

The five remaining oars dug deep.

Forty paces from shore and another cascade released.

Most fell short, but not all.

With a gasp, Joseph grasped the side of the boat. A bronze tipped arrow had found its mark. The top of his right leg bloomed red around the shaft and its heavy evil head penetrated from beneath his calf.

‘Row men, row. We’re depending on you,’ he shouted.

Panting, Joseph took a final look ashore. They were out of range. Thank you Lord.

He snapped the fletched arrow shaft close to the skin, tore his right shirt sleeve off at the shoulder and tied it over the wound. Limping, he gingerly made his way aft, patting each person manning the oars as he went. ‘Well done, all of you, no one could have done better. Keep it up, tell me when you’re tired and we’ll change over.’

Despite their distressing ordeal, he was gratified to see his people focussed and banding together. Steadying themselves against the rocking swell, they were easing the two dead under the cross-slats that served as their seats and into the lowest part of the boat. An intelligent move. The time for sensitivities would come later. Unwittingly, their fallen friends would probably save the lives of the rest of them. Acting as ballast they would help keep the craft from capsizing.

There was no sign of the tempest easing, if anything it appeared to be getting worse. The sky was getting darker, the cry of the wind more insistent. To Joseph it seemed a chorus of angry voices, trapped in hell, were intent on being heard. Catching Simon’s eye he gave the instruction for half-sail. It made sense to make the most of the prevailing wind, in spite of its strength. The faster they could make northern shallow water the better.

A feeling of faintness from blood loss flooded over him. He glanced over the side. Galloping white horses crested each and every wave and each of them foretold danger. They were evidently reaching the middle of the channel. In a flash of lightening he caught sight of another of their boats. A fleeting glimpse. It was fairing no better. They had also raised sail; unfortunately too much sail for the conditions and the port side of it had torn, flapping uselessly against itself. He gestured to all of his own passengers to ease as far from the boat’s centre-line as possible. It was about to get rough.

Skimming from crest to crest the boat quickly fell out of control. In answer, Simon tossed the sea anchor, a conical leather bucket designed to drag the stern square to travel, overboard. It had the desired effect. Although progress was now slower, command was just about possible.

The wind began to contradict itself, seeming to slam into them from the west and then from the south, then from both directions at once. It looked to be expending energy in self-destruction, driven suicidally to extinguish itself with its own fury. Whirlpools formed as a result. Through each vortex the nose of the craft whipped one-way and then the other, like a demented snake. From wave ridge to trough it crashed, and with each new valley came a fresh cascade of sand leaden water intent on forcing them under.

Frantically with cupped hands, plates, stitched leather bags, anything they could lay their hands on, everyone set to bailing, desperate to remain afloat. To the boat with the torn sail it would have appeared epileptic, a frenzied ballet of uncontrolled arm movements flailing hysterically in panic.

For an exhausting and agonising hour it seemed they would fail, then gradually, the deep central channel shallowed, the wave wash reduced and the level sloshing around their legs began to decrease.

Joseph tore his remaining left sleeve free, soaked it overboard and tied it about his nose and mouth. In spite of the battering the craft had received, it had acquitted itself well, yet had assumed its own unique and distinct aroma. A fusion of fear, hopelessness and vomit. Barely a passenger aboard had managed to contain the contents of their stomachs.

He could see the signs of resigned defeat begin to appear on all but a few faces, the inevitable result of seasickness. Something had to be done. It was a risk. He moved three of the heaviest further back into the stern and raised full sail. With the driving wind having swung to their backs the stem rose and he could feel the hull glide. With each gust the boat gained speed. The more they bailed the faster it moved. At this rate landfall would be only minutes away.

A strain of raised eager voices reached him. Although vague and imprecise they sounded joyful and vital. Searching earnestly for them through the shifting curtain of rain, his spirits soared. Land was in sight. At least two of their eight vessels had beached and the shore quivered with indistinct beckoning forms. They would make it.

Two hundred metres, a Roman stadium from safety, Simon gave the command to steer north. The boat, broadside to the flow, bucked and kicked like an unbroken stallion in the swell.

With a sudden jolt, it stopped dead. A sharp distinct crack sounded out above the roar of the roiling waves, all aboard pitched forward and a slow leak appeared at the base of the prow.

‘Hold tight everyone, we’re nearly there. We’ve run aground, nothing to worry about,’ called Simon, loud and clear. ‘Plant the oars vertical, see if you can push us free.’

The boat rocked erratically under the oarsman’s efforts. As each of them stood to gain greater purchase, the mother of all waves struck. Unsteadied by the high centre of gravity the seaward edge of the boat raised perilously, teetered vertical and collapsed. The capsize was total. With no heed for life or limb the vessel spilled its occupants and contents into the river.

Initially shocked and gasping at the coldness of the water, Joseph managed to surface. He shook his head clear. Tentatively he searched with his feet for the riverbed. It wasn’t there. The sandbank must have been just that, a bank, an anomaly on the base of the river.

He was drifting.

He could see the upturned hull. Most of the passengers had succeeded in grabbing hold of it, and those that could swim had control of the mooring rope, attempting to tow it to shore. With the help of the people already safe trudging out to meet them, they would surely make it.

With a faint twinge of regret he considered the contents of his lead capsule. Lost for ever to the clutches of the river’s muddy depths. Such a pity no one else would get to see it. In a world filled with pain and suffering, so much enlightenment could have come from it.

He shivered.

He could feel the biting cold of the river sapping his strength. He attempted a stroke for shore. Weakened significantly by the wound, he found he had barely the power to breathe, let alone swim. A whispered prayer found his lips. Surely someone would see that he was missing and come to his aide. He closed his eyes for a second. The action of doing so filled him with peace.

‘Joseph…Joseph…’

Someone’s calling me.

‘Joseph…’

Tentatively he opened his eyes. He was under water. Sinking. Visibility was so pitiful he could barely make out his own body. He likened it to gazing into a miasma of a thin brown soup.

Who called?

The water ahead of him began to clear.

I’m hallucinating. The form of a familiar man was materialising before him.

‘It has been a long time, hasn’t it?’

Twenty years or more. In all of that time, He hadn’t aged. The last instance he remembered seeing Him as close as this had been during the wondrous night of His ascension.

With a loving smile the man reached out and took him by the hand. ‘Friend. All of your life you have served me well. Permit me to do the same for you now. Please, come with me.’

2

The Find

10th June. North Bank of the River Severn estuary, South Wales, UK.

Theodore Webb cursed. Not for the first time today, only this time it meant a muddy trek back to the truck. The signal in his headphones was now so faint he could barely hear a thing.

Bloody batteries. This kit’ll take some getting used to.

He slung his anniversary present, a somewhat complex Minelab CTX3030 metal detector onto his shoulder and headed back. They’d unpacked it last night together, and what a wonderful night it had been. Her expression at his delight; pure gold. Worth more than any gift she could have given him.

By all accounts it was capable of distinguishing any manner of metals from the surrounding earth, yet thanks to the indecipherable instruction manual, today’s sweep, with the automatic setting, had had to suffice until Alex, his eldest, could guide him through it. The unit came with two lithium ion cells and the other was drawing charge from the battered Toyota pickup’s cigar lighter.

It hadn’t been a bad morning, in spite of the chill in the air. Two silver coins. Denarii’s, from the reign of Nero dating roughly to the late 50’s AD and a Sheffield plate shoe buckle, probably Georgian.

The whole area was steeped in Roman and medieval lore. A treasure trove, especially if you knew where to look. After a decade of combing the area Theo knew where to look and considered himself an expert. It had been heavily populated since the middle of the first century and Roman finds were everywhere, often in the most unexpected of places. The footings of roman walls were his favourite. In his experience, it was within a metre of the walls that the most lucrative pickings could be found. It wasn’t that much of a stretch to imagine a soldier’s purse snagging on a rock or implement of some kind and spilling its contents without notice.

The location for today’s excursion he’d chosen from a few hours pouring over Google Earth. The satellite images gave a faint indication of a settlement, possibly a port, two miles south of the old fortified enclosure of Venta Silurum at Caerwent. It had once been a Roman town, close to where the river Severn ran before silt and flood deposits had moved its course to its present day position.

Theo chose to skirt the ploughed field rather than trudge across it to give himself a moment’s reflection on the coins. Most unusual. Coins dating from the Nero period were uncommon in Britain as more permanent settlements began to form twenty years later. The case in point being the fortress of the second Augustan Legion at Caerleon, established sometime in the mid 70’s AD and a mere half day’s march away to the north west through Wentwood.

He scanned the horizon as he walked. He could see the new Severn bridge from here. A fantastically imposing structure, much more impressive than its elder brother hidden a few miles further upstream around the headland and the view across the estuary to Aust cliffs was just making itself known through the thinning morning mist.

Theo checked his watch. Just coming up to nine. June would be up soon. She always slept in on a Sunday morning and he had every intention of making today special. Anniversary special. Who would have thought it, thirty five years and never a crossed word.

If only her health matched her enthusiasm for life.

Assuming the doctors were right, this time next year he’d be alone. It was so unfair.

He swung the pick-up door open, perched on the drivers seat and dangled his muddy boots outside over the sill. The coffee from the thermos was still hot, thank God. Warming his sixty year old palms gratefully against the outside of the stainless steel mug he took a tentative sip. It was just about right. Another sweet mouthful and he nestled it dead centre on the ancient ring stain on the centre console and reached for the battery. The charger’s LED light showed green, indicating full charge. He unclipped it and swapped them over. Theoretically the fully charged battery would give him a solid eighteen hours searching, assuming of course he switched it off between uses. Something he’d forgotten to do last night.Getting old? Or was that senile?

He tossed a penny on to the earth a metre or so from the truck door, got to his feet again, snuggled the headphones back over his ears and wafted the circular detector head across it.

His ears were instantly assaulted with a powerful screech.

Odd!

The digital LED display showed a signature he would have normally associated with lead.

He threw another coin, a two pence piece, a pace to its right. Steel. A two pence coin was 93% steel, 3% copper.

That was okay.

He swung back to the penny. Still lead. He picked it up, clamped it between his teeth and bit down. Perhaps it was a fairground fake. No. It was hard, unyielding. A typical one pence piece.

Baffled, Theo switched off the machine and powered it up again. Maybe a reboot would clear the anomaly. Again he scanned the area where the penny had been. If anything, the signal was stronger.

This time he registered the depth. What ever it was, it was lying about thirty centimetres below the soil surface.

With a bewildered expression on his face, he unclipped the trowel from his belt, stooped to his knees and began to dig.

The soil was heavy, mostly compacted silt.

A minute’s excavation and the trowel tip began to scrape. A further minute and a shaft of dull grey revealed itself. A lead pipe. A half metre long, roughly tubular, flattened fractionally in its centre.

His first thought was drawn to Roman plumbing. After all that’s where the material got its name from; plumbum. He took the stiff brush hanging from his belt to better see the ends. Strangely they were both capped with some form of stopper, probably glass, although they were so badly encrusted, it was hard to be sure. Below the stoppers, where the lead folded back on itself to create rigid lips, were what appeared to be a pair of badly corroded soldered buckles.

He scraped carefully along the tube’s length to examine the soil. A darker brown band began to appear. Evidently the decayed remnants of a leather strap. It was a container.

Theo took out his small camera to photograph the find in situ. He didn’t really know why, but his heart began to race - his subconscious tripping over the possibilities of what might be inside.

Taking a gentle grip with his spanned left hand he rocked it from side to side to ease it free. It was decidedly heavy. Twice he tipped it, end on end. There was indeed something inside. He could feel it. Faint thuds as the contents shifted and slid against the caps.

His first thought was to take a knife and prise at one of the ends. He stood, stepped back to the truck and flopped into the driver’s seat. With the tube on his lap he drew his pocket knife from his trouser pocket, unclipped the blade and paused it over the cap joint. What if the contents are fragile? Could they decay in contact with air? He closed the blade.

3

Roman Seals

10th June. “Driftwood”, Llandewi, South Wales, UK.

It was a great day for travelling. Clear crisp air, sixteen degrees and a deep blue sky peppered with a smattering of puffy clouds. Honor had insisted on driving and Alexander sat relaxed in the passenger seat of her BMW M3, top down, mulling over whether to cook his parent’s anniversary lunch or take them out to a local pub. With the M4 behind them and the curves of the A48 ahead, she appeared to be enjoying herself, playing, putting the skills he had taught her around Brand’s Hatch into practice. And who said track days were a waste of money?

Llandewi castle came up on the left. They were close. He spotted the drive to “Driftwood” on the right and she turned in. The house, his home for twenty years, had risen a century ago as two cottages. Since then they had been knocked through and extensively extended. Surrounded by two acres of landscaped woodland and flanked by fields containing horses, nowhere else really felt like home.

Theo was waiting for them. The one thing he could always count on was Alexander’s punctuality. He glanced at his watch. Eleven on the dot. As expected. Like every other time he stood, arms cresting the braced five bar gate at the foot of the drive with Heathcliffe beside him sticking his black button nose between the slats. A megawatt smile of greeting illuminated his face.

With Heathcliffe’s first bark Maverick was awake from his recumbent sprawl across the car’s rear bucket seats. He sniffed the air, recognised where he was and wriggled upright. A second later and he was dancing excitedly in Alexander’s lap, slapping his tail back and forth across his face, a fuzzy manic metronome on steroids. To escape the assault Alexander opened the car door and let him out. He watched enamoured as Maverick took a few measured strides, vaulted the gate and disappeared up the path in a whirlwind of delight. The sight of two border collies frolicking with carefree abandon was definitely one of life’s greatest pleasures.

‘Hi Dad, you’re looking well, looking smart too,’ he greeted.

‘Your Mom made me change. You should have seen me earlier, a proper scarecrow, muddied from top to toe. Who’s your friend?’

Honor joined them and Alexander took her hand to indicate she was more than just a friend. ‘Honor, meet my father. You can call him Theo, everyone does, except me and Saskia. Dad, this is Honor Aston, my girlfriend.’ He lowered his voice to a stage whisper. ‘She’s a little nervous. Meeting the “parents” so to speak.’

‘Nonsense, come here girl and give me a hug.’

The gesture put Honor instantly at ease, as did the waft of Aramis aftershave. It reminded her of the comforts of home, snuggling close to her own father as a child. ‘It’s a pleasure to meet you.’

‘The pleasure is all mine. Come inside and meet the Mrs. I confess I’d be lying if I said I didn’t feel that I knew you already. You’re all Alexander talks about, when he calls.’

With Honor captive, and he all but ignored, Alexander climbed into the car and followed them at a crawl to park beside the back door. As they went inside he smiled. His Dad was good at this. It didn’t matter who they were, he had the knack of making people feel important and comfortable in his presence. Before choosing early retirement to look after June, he’d spent the latter part of his life lecturing, moulding minds and instilling within them an appreciation for the glories to be found in the classics. His fascination with Homer, Virgil and Ovid had probably been responsible for drawing his wife to him in the first place.

Alexander bleeped the M3 remote, passed through the kitchen, and guessing where they’d be, entered his father’s study. Little had changed since his last visit. It was a comfortable spacious room with two Chesterfield couches, a computer station nestled in the corner and an illuminated artefact inspection table along most of the right hand side. On the soft shaded lemon walls hung an array of picture frames. A few travel photos, several displays of Roman coins encased artistically behind glass, his and Saskia’s graduation pictures, and a formal image of his pass-out parade at Sandhurst – a shot of thirty or so young men and women in full regimental parade dress on a benched terrace. Every time Alexander saw it he cringed with embarrassment. He was the only one flaunting a grin from ear to ear.

Both his mother and sister were seated and Honor, standing, was peering intently over his father’s shoulder at a dull grey tube nestled on a bed of soiled newspaper.

‘Come and sit by me and give your old mother a kiss,’ said June.

Dutifully he obeyed, kiss first and then a soft slink into the yielding leather between two of his three favourite women in the world.

‘They seem to be getting along,’ he stated, addressing his remark to his mom whilst looking at his dad.

‘He’s been out with his new toy. Found a lead pipe, he says it’s Roman. I think it’s probably off the church roof, they’re forever raising money for it. What is it about church roofs? Why do they always seem to need replacing? Even now, there’s a thermometer board outside Saint John’s. I wouldn’t mind betting, that’s for the roof. ’

‘It doesn’t look like a church pipe to me.’

‘Well whatever it is, it’s one false alarm after another. You should see some of the junk he brings home. The garage bin’s full of it. Still, keeps him happy I suppose, that’s the main thing.’

He never really knew when to take her seriously. They were as bad as each other for banter. With both parents gifted, inveterate, verbal pranksters, it was a wonder he’d grown up with a sane cell in his body. But then again, probably he hadn’t. ‘How’s the chemo going?’ he asked.

‘I don’t want to talk about that. I’d much sooner hear about Honor and the museum.’ Then whispering she added, ‘She’s lovely by the way, you should keep this one.’

‘I intend to.’

He didn’t need to recap on their adventure together over the Christmas holidays, where Honor and he had discovered the ancient Pharaoh Akhenaten’s tomb, as this was old news to her, and he had no intention of making her aware of the event’s that followed, they would only cause distress. Instead, he concentrated on bringing her up to date with the progress of the new museum situated on the plain of Amarna. Dedicated to Akhenaten, the treasures recovered from his tomb were gradually and painstakingly being transferred inside to safe and secure glossy display areas.

All the time while Alexander was talking, Saskia remained silent. He glanced at her in the midst of describing how the golden chariot would be positioned and fell lost for words. ‘Are you alright?’ he asked. ‘You’re awfully quiet.’

Wistfully she shook her head. ‘Jet lagged, that’s all. Nothing a good night’s sleep won’t cure.’

‘We need to clean it thoroughly,’ stated Honor. ‘I’ll need some white vinegar, distilled water and stiff brushes.’

‘In the garage. I’ll fetch ’em.’

As Theo passed Alexander he gestured with his thumb in Honor’s direction. ‘She’s good at this stuff, isn’t she!’

‘She aught to be, or she’s wasted five years of her education.’ He laughed.

Honor gave him the look. He stopped. She laughed.

With Theo on a mission, she returned to picking carefully at the left-hand end of the tube with one of his dentist toothpicks. It was the end that seemed to be in the better condition of the two. Before her, on a bed of cushioned red velvet, lay Theo’s vast collection of artefact preparation instruments. It must have taken years to collect such a wide variety. Some of them would not have looked out of place in the torture cabinet of the Marquis de Sade.

He returned with a huge fish poaching tray, a couple of old Harris paint brushes, a large bottle of the vinegar and a gallon container with a pouring spout. ‘Will these do?’

‘Perfect. Mix the vinegar and distilled water in a ratio of one to one and I’ll pop outside and get as much of the muck off it as I can with the hose.’

Honor carried the tube through the kitchen and out to the garden. She uncoiled the wall mounted hose and began to jet its flow at the encrusted chunks of silt adhering to the lead body. Before long the pipe had shed all but its most intransigent clumps, revealing a seamless cylinder. She took it back to Theo and eased it gently into the vinegar and water mix. ‘Well, it’s not a Roman plumbing pipe,’ she stated.

‘What makes you say that?’ he asked.

‘There’s no seam. Roman pipes were made by folding sheets of lead and then sometimes sealed along the joint with solder. This one has been cast from molten lead into a cylinder. If it’s Roman, it’s pretty strange.’

Disappointed at Honor’s revelation, a cloud of dejection fell over Theo’s face. ‘You’re sure?’

‘Yes. There should also be an emperor’s insignia stamped somewhere on it, and there isn’t. Also, look at the level of corrosion. There’s very little, just the odd patch of white lead rot. That says to me that it’s probably a lead-silver alloy.’

‘So, it’s not Roman then?’

‘It could be, but it would be unusual. If it is, it would have had to have been made by a gifted metals merchant! One positive point though, if there’s something inside, it’s most likely bone dry.’

After careful cleaning with the brushes, Honor lifted the container from the tray, drained all of the liquid mixture from the outside and gave it a final swill with pure distilled water. She passed it to Theo for drying.

‘You should open it,’ she said. ‘It’s your find, after all.’

Theo fetched a pillow from the guest bedroom, nestled the tube onto it and began prising at the junction between one of the glass stoppers and the body. Gradually, and with only a little damage to the pipe, the pale green stopper came free and tumbled to rest on the white linen.

He peered inside.